Writing

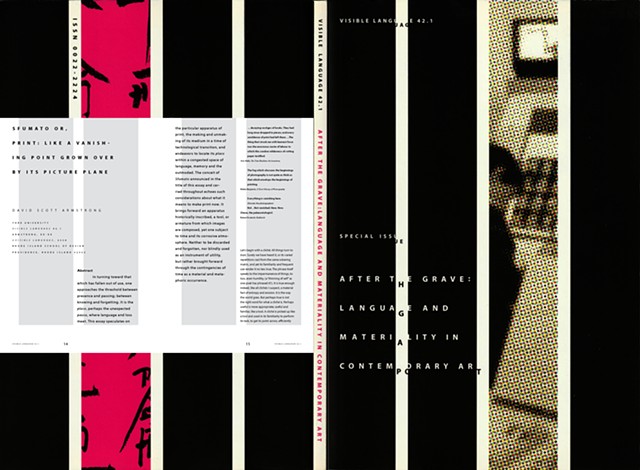

published in: After the Grave: Language and Materiality in Contemporary Art, Visible Language issue 42.1, 2008, Rhode Island School of Design. (co-edited by David Scott Armstrong and Patrick Mahon).

“... decaying vestiges of books. They had long since dropped to pieces, and every semblance of print had left them. ...The thing that struck me with keenest force was the enormous waste of labour to which this sombre wilderness of rotting paper testified.”

-H.G. Wells, The Time Machine: An Invention

“The fog which obscures the beginnings of photography is not quite as thick as that which envelops the beginnings of printing”.

-Walter Benjamin, A Short History of Photography

“Everything is vanishing here.”

(Sinnott, the photographer)

“No!…Not vanished. Here. Now.”

(Dawe, the palaeontologist)

-Robert Kroetsch, Badlands

.

Let’s begin with a cliché: All things turn to dust. Surely we have heard it, or its varied repetitions cast from the same sobering matrix, and yet its familiarity and frequent use render it no less true. The phrase itself speaks to the impermanence of things, to loss, even humility, (a “thinning of self” as one poet has phrased it ). It is true enough indeed, like all clichés I suspect, a material fact of entropy and erosion. It is the way the world goes. But perhaps true is not the right word for what a cliché is. Perhaps useful is more appropriate; useful and familiar, like a tool. A cliché is picked up like a tool and used in its familiarity to perform its task, to get its point across, efficiently and with economy. And yet if tools, words, and such technologies were nothing more than instruments of our will, they would inevitably become vacant specters when we put them down. Their decline then to the status of the overused and outmoded would render their utility as dust, like “coins which have lost their embossing and are now considered as metal and no longer coins”, as Nietzsche figured it. This is language becoming unlike itself.

All things turn to dust. Even the printed page, as our unnamed time traveler tells us. Ink and paper are translated into a language of dust. And what of the common multitude of everyday currencies (words, tools, ideas), these things that circulate within language, but now drift beyond their conventional familiarity and utility? Once residing in language, giving it shape and body, they now skirt the edges of language and interest. Are they, in spite of themselves, consigned to withdraw further into obscurity; lost to the hyper-speed and disposability of our present experience? As Don McKay reminds us, even when Nietzsche is describing the illusory ground on which truth and language are established, he reaches for the very language he doubts, in the form of his own metaphoric coinage, to make his point. It is in such vulnerable moments, notes McKay, that we are unwittingly reminded of the “apparatus”, the “rickety tool” of language “working away at an impossible task.”

This essay speculates on the particular apparatus of print, the making and unmaking of the medium in a time of technological transition, and endeavors to locate its place within a congested space of language, memory, and the outmoded. The conceit of Sfumato, announced in the title of this essay and carried throughout, echoes my thinking about what it means to make print now. It brings forward an apparatus historically inscribed, a tool, or armature from which images are composed, yet one subject to time and its corrosive atmosphere. Neither to be discarded and forgotten, nor blindly used as an instrument of utility, but rather brought forward through the contingencies of time as a material and metaphoric occurrence. In turning toward that which has fallen out of use, one approaches the threshold between presence and passing; between knowing and forgetting. It is the place, perhaps the unexpected pause, where language and loss meet.

.

There is little question about the degree in which the printed word and image have proliferated within the realm of human communication over the last half millennium. The predominance of the book within the cultural history of the West serves as a kind of gravitational centre at which the ambitious flights and follies of human knowledge have found a nesting place. And it is the various means of reproduction, print technologies, which have facilitated the mobilization and dispersal of this knowledge: projecting words and images outward across an expanding geographical and cultural terrain. Now, somewhere between the pull toward the vanishing point of the past, and the multiple distractions of an over-mediated and all pervasive information culture, sits the book, the imprinted page, in all its various forms — both complicit and at odds with the world of our making. Our cultural landscape is settled with the tracings of paper and ink.

The proliferation of printing and other reproduction technologies has bestowed upon the 21st Century a vast accumulation of stuff — significant, ephemeral, undecided. It is by proxy of these reproduction technologies that we have inherited a packrat ethic: allowing a swell of stuff to pile at our feet; accumulating a wreckage of the past. So, blindly, like Walter Benjamin’s angel of history, we are propelled toward what is ahead. Yet the question as to what we must do with all of that past stuff is ours; how do we make sense of it and where do we place it amidst the priorities of the present? The “fog,” with which Benjamin begins “A Short History of Photography,” invokes a climate of reproducibility, and the difficulty in gaining a critical proximity to the past in a present so consumed by its own “accelerated pace of development.” This unrelenting accumulation of reproducible “stuff” speaks to a decidedly conflicted relationship between the present and past, between the proliferation of technology and its obsolescence — a conflicted stance very much felt, perhaps even amplified in our present moment of instantly consumable information. The insistence on the ever “new” renders its predecessor as old, past, and outmoded. It is this very notion of the congested atmosphere of modernity that Benjamin articulates in his photography essay in relation to the more critical and conflicted notion of the aura. Here, the aura not only suggests “[a] strange web of time and space: the unique appearance of a distance, however close at hand,” but it expresses the very impulse of a rapidly advancing modernity to clear itself of the “sticky atmosphere” of the past. It wants to “…suck the aura from reality like water from a sinking ship.”

For Benjamin the aura is a “long exposure” to time and space, a patina that grows into its surroundings — but also more wearily grows a layer of dust like a tired, hackneyed cliché. It is a house to be swept clean, waiting empty for its new tenant. Yet the aura, like the inevitability of dust, is not to be so easily swept aside, but rather lingers as a residue and remainder, settling around the edges of reproducibility.

Georges Didi-Huberman sees the aura in Benjamin’s larger oeuvre as a “response to a transhistorical and profoundly dialectical experience.” Less like a death (of the aura) than an agent of its own decline, (its “falling away”, but not its disappearance) he sees the aura as allowing a slipping underneath the work of art. For Didi-Huberman, the aura constitutes itself not through human will alone or by the authority of that which imposes itself upon, but is made, unconsciously; supposed from underneath the distractible, disposable “stuff” of our time like the involuntary reflex of material memory, or, in a curious turn, like an act of respiration. It is “the air that surrounds us as a subtle, moving, absolute place…and makes us breathe.” This breathing space of the aura (an “appearance of distance”) is possible for Didi-Huberman by a bringing forward of the presence of human labour and of the contingency of time in the form of the trace (defined by Benjamin as the “apparition of a proximity”). This “auratic trace” occurs where appearance and apparition, and distance and proximity are brought together. In this sense, the aura can be seen as the “air,” the movement of contingent stuff — histories, associations, corrosions — that settles and circulates as an “other presence” around the work of art.

This supposed “other presence” of the aura can be seen in the individual works of two Canadian artist: Blair Brennan, and Janet Cardiff. In Brennan’s 1996 work, Perish Like the Word, (reproduced elsewhere in this issue) the incantation “ABRACADABRA” is branded from heated, hand forged irons directly into the wall in the overall form of an inverted pyramid (with the full word forming the top line, then each subsequent line decreasing by one letter with the single letter “A” at the bottom vertex). Leaving not only a scorched combination of magic letters and an auratic trail of sooty smoke on the wall, the branding irons themselves are arranged on the floor below the branded trace to give physical weight and labor to the burnt, smoky apparition. The traces of smoke, released and recorded around each individual letter during the formative moment when the hot iron contacted the cool wall, seem to suspend the “utterance” at a point between forming and perishing. The smoke is extra-linguistic matter, in excess of the word, the way breath escapes around words as they are spoken.

In her installation, To Touch, (1993) Janet Cardiff positions in the middle of a large room an old wooden table. It resembles something like a work table, heavy, crude and presumably marked and weathered by a history of use and time. Spot-lit by the room’s only light and attended by a simple directive given us upon entering the gallery space, one is compelled toward the table, to lean against it, to touch and run one’s hands over its varied surface. Upon touching the table one begins to hear voices emanating from a series of speakers that line the room’s darkened perimeter. They tell stories, both intimate and banal; their sounds overlap and interrupt each other, floating around various parts of the room and corresponding to the measure of physical contact with the table. They accumulate, filling the room with a murmuring noise.

These physical acts of touching and imprinting make the viewer acutely aware of both their own presence and the “other presence” of a previously inscribed material event. Didi-Huberman calls this encounter with both the “now” and the “then” of a work of art, a “dialectic of place,” a so-called thickening of the air, “making us touch depth.” The depth we are brought to is not one within an illusory space but in an embodied place: a place of history, association, and material contingency. It is a depth and not a surface that we touch, for it is a decidedly temporal experience, marking a duration inscribed on and beyond its surface. It is the disembodied voices that linger and disappear around an object in Cardiff’s work. Brennan’s branding irons (repeatable matrices) could leave their traces elsewhere, (any surface could become a receptive ground), for these implements are not tied to a place, nor do they transcend the need for one, but their impressions make a place, or rather summon a place from elsewhere, making it a transitory site of convergence, compression and release. This creates a “depth of place,” a felt dilation which focuses material presence; it is also a provisional one which posits an eventual erasure and dispersal. As a temporal appearing and disappearing act of sorts, the aura is conjured up in our very presence, while leaving us wondering about the seeming impossibility of it all.

.

“Just as the art of the Greeks was geared toward lasting, so the art of the present is geared toward becoming worn out.”

-Walter Benjamin, Theory of Distraction

Perishability is the mode of our times. And yet, perhaps for the sake of maintaining a cohesive sense of identity or for fear of losing it, the perishable also has a type of safety net that trails in its wake, gathering up, sorting and sifting through this jettisoned stuff. The capacity for remembrance, whether via human memory or with human-made memory devices, is part of our own enmeshed hardwiring. We throw away so that we can remember, or, is it that because we remember, we can throw away? It seems so perfectly “Newtonian” in its equilibrium; where every action produces an equal yet opposite reaction. It seems a perfect equation of spent energy saved — if it were not for the sense that the growing world of spent matter has gotten the better of us.

“The feeling for the inert has a special significance in our age, in which the obverse of the capitalist drive to produce ever more new objects is a growing mountain of useless waste, used cars, out of date computers etc, like the famous resting place for old aircraft in the Mojave desert. … Nature and industrialized civilization overlap, but in a common decay: a civilization in decay is being reclaimed, not by an idealized, harmonious Nature but by nature which is itself in a state of decomposition.”

The foregoing is from Slavoj Žižek; it bears noting for a couple of reasons. It speaks of the obverse of (over) production being the inert, linked by a “common decay,” which, as Žižek goes on to describe, is a form of delay or waiting.

The other thing to note? How the sentence hinges on the word like. One can almost imagine the writer in mid thought, after initially laying out the idea and a supporting list of examples, pausing in a slight or broad moment of inertia, searching for the thing that will stretch the thought a little further. What is it to be like something? Like is a point of comparison — “this is like that” — a form of linguistic reach. But when do we reach for it? In those paused moments when the thing we are attempting to describe, or the very thought itself, seems somehow incomplete, too obscure or inert to hold its own. We reach out with this comparative “like” when we are confronted with an “unlikeness,” when the things of the world and of our attention no longer bear easy or immediate resemblance. Yet, it is not just the like that captures the interest here, but that which immediately precedes it: the beginning of a list followed by an inference of its continuation — et cetera.

Let me retrace the arc of this rhetorical passage from the beginning: it starts with the presentation of the idea of inertia and a “growing mountain of waste,” continues on with its own growing list (…etc, and so on…), then takes what seems an imaginative leap beyond descriptive inertia toward something akin to a lively poetic image. It traces the path of entropy, where things fall apart under the force of their own cumulative weight, yet endeavoring in that very pause to find a restoration of language.

The relevance of this arc is in how we might consider our current preoccupation with technological growth and entropy and how the medium of print might fit into this framework. Print technologies experienced something of a explosion in the art of the 1960’s, a period where the idea of technology itself, and its links to an increased industrialization, reproducibility, and mass culture, were met with an ambivalent mix of both optimism and resistance. Pamela M. Lee explores that decade’s ambivalence, focusing on art and technology and a profound reformulation of our relationship to time. She see in the art of this period, (and one can easily speculate how it extends into our current time as well), a preoccupation with time, describing a future bound to technological recursiveness, enacting a repeated cycle of “novelty and obsolescence, innovation and outmodedness”. Caught in this endless repetition, the avant-garde faces its own crisis where its forward advance is brought to a standstill — becoming stuck in both time and in its own contradiction, without recourse to transcend it. Time and experience become increasingly compressed to the fleeting, perfunctory “everyday,” to the particularities of the moment always repeating, never ceasing. It is a crisis of being unable to transcend the moment.

The notion of “medium” in art has similarly undergone a radical shift in thinking, bearing the effects of a far reaching criticality toward the inheritance of past categorical conventions, and its opening toward time and novelty. “A medium,” notes Charles Bernstein, “is an ‘in-between” in which you go from one place to another, but also the material of that in-betweeness”. Conceived as such, a medium is on the one hand a vehicle: a means by which something is carried, represented or recorded. It relies on the efficiency and usefulness it may have for a user in order to travel. A medium is a tool, marked by the ability to produce a likeness of something, rendering the material fact of the work transparent. With a likeness one is less aware of the work’s physical material properties (ink on paper, paint on canvas, projected light on screen), than of the subject matter (a landscape, still life, or portrait). On the other hand, to produce an unlikeness is to make visible the material fact of the work, such that it does not look like anything other than its own unique appearance. A tool’s utility may be based on the promise of transcending the fact of its materiality, yet there is a way in which contingency and temporal undoing reasserts material’s “other presence” back into the mix.

Where does the medium of print fit into this art and technology nexus, and its recursive state of inertia? Scanning the decades since the so-called “print boom” in 1960’s art, we may no doubt think most prominently of Warhol. But perhaps, reaching further back, the 18th C. Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi might be invoked here with his intricately crafted engravings of the architectural ruins of ancient Rome. Rendered through an “architecture” of engraved lines, dots and dashes, these prints describe a past world of structures falling and collapsing in upon themselves, yet opening toward something beyond the order of architecture — toward a long exposure to weather, erosion and time. Haunted by its former utility, this represented architecture returns to an elemental state: it becomes a pile of matter, speaking not of utility, but as an index of its once inscribed use. Piranesi’s prints take the ruins of Rome as their subject, but are not themselves ruins. Warhol’s, on the other hand, are just that: their very surfaces bear the traces of a faulty medium collapsing under the weight of its repetitions. While distinguished by this difference, both artists present an essential aspect of print in relation to material inertia: print, it seems, is forever becoming unlike itself.

Jumping forward, the printed paper stacks of artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres, with their potential for endless renewal and dispersal, evoke another sense of loss and restoration through both the technical and social apparatus of print reproducibility. In works such as Untitled (The End), and Untitled (Blue Mirror) we find both an authoritative self-sameness fortified as sculptural mass, and a quiet self-effacement in being “spread out into a thousand small instances.” As a monolithic form, a focal point made up of an unlimited edition of prints placed in a gallery space, the work constitutes a site that is continually refilled and emptied out, or displaced as people are welcome to take a print away from the stack. The relatively stable body of the stack sheds its paper like layers of skin. The manner in which these mute prints (they are characteristically “empty”, covered by a single flat colour, or a simple border that frames a blank expanse of paper) yield to circumstance makes their emptiness fill with the minutia of everyday particularity. (What happens to these prints after they leave the stack is an open question.) From their origins as mass produced likenesses, made to be disseminated and displaced, (as in the case of any edition), they grow into their new surroundings. Whether treated as art or “common” ephemera, they acquire new contexts: becoming unique unlikenesses. (Consider here Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, a work enshrined by its auratic uniqueness, but also one of the most reproduced works in Western art. As such, it has become a ready site for growing both a moustache, and an aura of unlikeness).

Print is most commonly understood, as a tool and a technology, with the intent and purpose of reproducing, storing, disseminating and communicating. It is to a large extent “known” for being a kind of supporting player, a mechanical apparatus placed under in order to reproduce other words, other images, other media. When compared with different, sometimes seemingly related media in contemporary art, such as photography, film, and digital media, and, of course, painting, there is a notable lack of critical, evocative writing on print as an art form. This produces a muteness that further underscores its present, yet hidden status. Unconsciously sensed, broadly implicated, but rarely stated or foregrounded, print, in many ways, still lingers underneath photography’s historical black veil on the other side, at the backside of the camera. And at this moment, its language and currency is perhaps being digitally devoured, like the worm which poet Irving Layton says must sing “for an hour in the throat of a robin.”

Yet print does not belong exclusively to the realm of human intention and utility, as simple textual and graphical composition. It instead bears the weight of language, facilitates it, repeats it and collapses, breaks apart under it. Reproducibility begets reproducibility… begets dust. In time, print settles (decomposes) into its surroundings to become a trace of its former self, an after presence that illuminates its own obscured absence. As such, the print as a trace of its own mode of production does not so much “speak” by means of graphical reproducible language, as it now operates to disturb its seeming utility, uttering out of the residue beneath the flood of language. Not just an aid to memory, it haunts memory. Lingering uncertainly, after the fact. Like a fossil formed under the pressure of time, the printed trace is a hollowed shell, an indicator of the body’s passing elsewhere. The body of print, subject to its own overproduction, overuse and dissolution, is itself over-printed by pressure, erosion, and time. Becoming a trace of a trace of an other.

After ruminating here upon several notions concerning print, language, and material inertia, I wish to make a broad assertion: language is restored by disclosing its materiality, by maintaining an irresolvable tension between its promise of transcendence with respect to making meaning, and the fact of its being unmade in time. In other words — language is invigorated by its mortality: a ceaseless process of making and unmaking itself.

What of the missing body of print — has it not always been the case? A material residue; a physical, yet vulnerable trace left behind — deposited in the wake of our own passing through the world? With the assumed authority of a fact, the act of imprinting speaks emphatically, ‘I am here’, in a manner that assures its immersion in a present reality and relationship to physical things, but also, almost immediately, speaks the uncertain and lingering ‘I no longer am’. Here, between identity and oblivion, is the transitional space that print marks: a terrain perhaps similar to that which consumes the body and language of A.M. Klein’s “outmoded” poet, the “nth Adam” of the modern world, who now forgotten…

makes of his status as zero a rich garland,

a halo of his anonymity,

and lives alone, and in his secret shines

like phosphorus. At the bottom of the sea.

Indeed, this is the hollowed-out dwelling at the heart of the print. An image of auratic decay, a sublimity, settling anonymous and under pressure, “[a]t the bottom of the sea.”

.

Robert Kroetsch writes that “[to] reveal all is to end the story. To conceal all is to fail to begin the story.” The very possibility of delineating beginnings from ends, or as quoted at the beginning of this essay, that which has “vanished” from that which is “here, now,” is rendered even more difficult in such reflexive, recursive times. Yet the question of where the historical print begins and whether its end is within our sights is a question for the history books. It is not my question to ask here. The more critical question, from my perspective, has to do with both the specific and transformative possibility of a medium, its making and unmaking through material and metaphoric contingency. Elsewhere, Kroetsch has written about beginnings and ends, or what he calls “the dream of origins,” in relation to the prairie region of Canada, the small town, and the farm as “…not merely places, [but] remembered places.” These “imagined real places” are places to be reinvented, retold, beginning again after the story has ended.

One such place for me is the site of my Grandparent’s homestead and its surrounding area in the Canadian prairie region of southwest Saskatchewan (just west of the city of Swift Current). The place itself is a very real site of economic, generational and geological change — mapped, carved and deposited into the landscape. But it is also a site of memory and erasure populated by those rusted, faded and weathered deposits of stuff often found half buried by topsoil drift and the overgrowth of prairie grasses left untilled by human need. It is a site reclaimed, in spite of its ultimate foreignness, by its surroundings. In these places of randomly clustered piles found in and around the quonset; “the dump” at the edge of coulee; and the “old kitchen”, one could find things half-lost to the past, half-familiar, yet strangely other. The used up, no longer needed, but nonetheless still kept stuff, particular to the plot of land that cradled it, offered it a familial proximity, yet set at a distance from the lived experiences of my grandparents.

The “old kitchen” was the only part of the original farmhouse that was saved from demolition in the mid 1970’s after the new house was built a mere stone’s throw away. In place of the leveled old house, and the old kitchen, which was eventually moved over by the quonset and raised up on railroad ties, now stands a yard light affixed atop a telephone pole surrounded by a flower garden (the site became affectionately named “the graveyard”). Viewed from its exterior, this old kitchen, which could not have been any more than eight feet squared in its detached state, now resembled a simple storage shed. A remnant itself as well as a shelter for the housing of smaller remnants — things not good enough for the garage, or basement, yet too good for the dump (enamel washbasins, steamer trunks, kerosene lantern) — the old kitchen ¬¬¬¬was itself the very same as the stuff that it contained.

Robert Smithson, in A Sedimentation of the Mind and in other texts, sees language itself as a form of material deposit and displacement. He brings to bear on language, art and its comparative industrialized landscape, its own material vulnerability, buried under the sediment of time and disuse.

The names of minerals and the minerals themselves do not differ from each other, because at the bottom of both the material and the print is the beginning of an abysmal number of fissures…. Look at any word long enough and you will see it open up into a series of faults, into a terrain of particles each containing its own void. This discomforting language of fragmentation offers no easy gestalt solution; the certainties of didactic discourse are hurled into the erosion of the poetic principle. Poetry being forever lost must submit to its own vacuity; it is somehow a product of exhaustion rather than creation. Poetry is always a dying language but never a dead language.

The farm “dump,” located in a hollow between two small hills at the top edge of the coulee, takes the form of poetic clusters; fissures and fragments of a past always dying but never dead. An aggregate mix of exhausted machinery and parts, tangles of cleared brush, barbed wire, fence posts, tires, and piled deposits of smoothed stones (ploughed up from adjacent fields) embedded and buried in the grass and dirt: this is the “poetic principle” to which print also attends. It operates at the edges of utility.

To acknowledge that our language is exhausted, and to do it in the act of using it is a quieting yet also lively undertaking. Print, as a kind of material memory, indicates “a dying language but never a dead language,” one that has fallen under the pressure of time. Prints are dust. They are the residue of an abiding presence. The potential for such a view heightens our critical awareness of the vulnerability of our language. How does our technological reach within the world resist reducing the world to the form of our grip? I am interested in the cultural span of print, in particular because it seems that now, due to its present material vulnerability, that its imprinting offer us less a fixing of the world than a tracing of its passage. In this regard, we might find the liminal traces of print embedded throughout our cultural landscape as a kind of memento mori — drawing us into awareness through the rumblings of its own uncertainty: where its dust reveals more than what language can hold. So we endeavor to locate ourselves through language, in a time and place troubled by displacement, deposit and erosion. Like the path of a retreating glacier: collecting, accumulating and transporting stuff picked up along the way, language leaves in its wake erratics that settle and grow into their new surroundings. (Perhaps this is not so unlike Da Vinci’s The Last Supper in Milan, where the “long exposure” of these fugitive materials to time and the effects of atmosphere’s invasive touch, seem perpetually in excess of the restorative measures aimed at rescuing the painting from the further degradation of its own material).

.

The sense of speed inferred by the once ubiquitous, now quite forgotten phrase “the information super-highway” can be considered in two ways: most obviously, the high traffic and rapid transit of information, but also the rapid movement of the phrase itself toward the status of cliché — tired, hackneyed and overused. The new road (or highway) is metaphorically built upon the old. The “road,” as a metaphor for the accumulation and transmission of knowledge, serves as the common ground of understanding — an old cliché upon which the construction and understandability of the new becomes possible.

In 1993 my Grandparents sold their homestead and surrounding land and moved to the city of Swift Current about 14 kilometers east of their farm. There are two ways of driving into town from their farm: there is the new, divided, four-lane blacktop #1 highway (a section of the main road artery of the Trans-Canada Highway), and there is the old, narrow, gravel-top “#1 highway.” The “old #1” is still maintained to some degree and is still used for local travel. The new #1 is used for local travel as well, for going to and from town, but it is mainly used as a way for travelers to quickly pass through the town — the destination always being some place else. If the new #1 is now noisy with traffic, with use, the old #1 is comparatively quiet. Yet, this distinction can also be turned around on itself: the old road, although now peripheral (or more appropriate to the metaphor: out of earshot), has become noisy, due in part to its disuse. It has become a source of background noise: car travel on this “washboard” road kicks up dust and gravel — its surface is easily dispersed. The new road is built for efficiency, for clear and unobstructed travel. Its smooth and uniform black surface differentiates itself from the landscape; local noise is reduced for the sake of quick passage. In relation to this, the old road is becoming increasingly noisy; becoming overgrown and weathered. The fields that border the road are beginning to encroach upon its edges.

There are at least two possible futures for this road: in time it will increasingly become a part of the landscape — reclaimed; or, it will be developed, “appropriated” as a suburban street. In the first scenario, like so many other prairie roads, it will act as a trace of travel, a memory of passage, yet will be no longer used as such. In the second scenario the road will lead through the suburbs — toward comfortable and leisurely detachment. When a road is no longer an efficient road but has become part of the landscape, travel is not so much denied as it is less determined by purpose. The old road is no longer used for efficient travel — to go quickly from point A to point B. It can still be used for travel, but for a meandering, slow travel. This is travel with a loss of differentiation. When the boundaries which direct intention are not maintained through upkeep, one travels through a dusty, bumpy field of noise. Travel becomes less directional, less about traversing space and more about inhabiting a place (settling, perhaps, like dust).

What happens to the old road of print after the new “superhighway” has diverted traffic? What happens to the old print road when it is no longer a road of efficiency and clarity? A tool may disappear in the familiar act of being used as a naturalized extension of the body, then surface again, to become visible: self-conscious with its slips, errors and accidents, eventually entering into an awareness of the body’s otherness; its mortality. What happens to outmoded technology, a de-familiarized technology, when its utility is no longer assumed? Is it reformulated, reconstructed within the shell of the new (using strategies of appropriation and postmodern pastiche and irony)? Does it go from being a main route to a side road? Is this old road left only for local travel and for Sunday drives? The new road is built for efficiency, speed and commerce: merchandise is the message carried along this path. Its lines are hard, clean and smooth: the channel is kept clean and clear. Obstructions (traffic) and disturbances (holes, weathering and erosion) are monitored to plan for continuous upgrading, countering loss and inefficiency. The old road becomes increasingly difficult for efficient travel. Travel on this road becomes both more particular (local) and less differentiated (dispersed). It is a route of digression away from the centre of activity. The road becomes a trace among a multitude of barely traceable others, among many contingent paths. Like a vanishing point grown over by its picture plane, in time the road becomes a field.

Notes:

Tim Lilburn, “How To Be Here.” Living in the World as if it Were Home. Dunvegan: Cormorant Books, 1999. 3-23.

Friedrich Nietzsche, “On Truth and Lie in an Extra Moral Sense”. The Continental Aesthetics Reader. Ed. Clive Cazeaux. London: Routledge, 2000. 53-62.

Don McKay, “Remembering Apparatus: Poetry and the Visibility of Tools”. Vis à Vis: Field Notes on Poetry and Wilderness. Wolfville: Gaspereau Press, 2001. 55-73. McKay’s thinking around the functionality of tools, metaphor and the wilderness beyond has been an invaluable resource for this essay.

The idea and technique used by Leonardo Da Vinci to achieve the atmospheric effect known as “sfumato”, (to vanish like smoke), was achieved by painting thin varnishes of black pigment over the surface of the painting, resulting in a blending of line, colour and contour. (See, John Moffatt’s, Leonardo’s ‘sfumato’ and Apelles’s ‘atramentum’. Paragone. July 1989. 88-94.) This sooty black material, collected from the impure combustion of oils, was a common pigment used in the manufacturing of printing ink. As such, one might think of how even by the 16th C. the European landscape and atmosphere was already beginning to be covered and permeated by an accumulating flood of printer’s ink.

I have drawn from Benjamin’s many writings on modernity, reproducibility, and the aura; particularly, “A Short History of Photography.” Trans. P. Patton. Classic Essays on Photography. Ed. Alan Trachtenberg. New Haven: Lettee’s Island Books, 1980. 199-216. See also, Illuminations. Ed. Hannah Arendt; trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1969.

Georges Didi-Huberman, “The Supposition Of The Aura: The Now, The Then, And Modernity,”. Trans. Jane Marie Todd, in Negotiating Rapture, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, 1996. 43-68.

Walter Benjamin, “Theory of Distraction”, Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Volume 3, 1935-1938. Ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings. Trans. Howard Eiland. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002. 141-142.

Slavoj Žižek, “Not a desire to have him, but to be like him”. London Review of Books. Vol. 25, No. 14, 2003. 13-14.

Pamela M. Lee, Chronophobia: On Time in the Art of the 1960’s. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004. 276. Lee draws upon Hegel’s notion of “bad infinity”, which indicates an inability to resolve, or sublate, the back and forth oscillation of the dialectic.

Charles Bernstein, “The Art of Immemorability”, from, A Book of the Book, Jerome Rothenberg and Steven Clay (editors), New York: Granary Books, 2000. 504-517.

See also Don McKay, where he writes: “It may take some break in the surface of experience… for us to see that tools exceed the fact of their construction and exemplify an otherness beyond human design.” (“Remembering Apparatus”, 57.)

Susan Tallman, “The Ethos of the Edition: The Stacks of Felix Gonzalez-Torres”. Arts Magazine. September 1991. 13-14.

Irving Layton, The Cold Green Element. 1955.

A.M. Klein, Portrait of the Poet As Landscape. 1948.

Robert Kroetsch. “The Continuing Poem.” Open Letter. Spring, 1983. 81.

Robert Smithson. “A Sedimentation of the Mind.” Esthetics Contemporary. Ed. Richard

Kostelanetz. Buffalo: Prometheus Books, 1989. 242-252.